“Peak times for New Orleans crime? Not after 3 a.m., data shows, despite doors-closed proposal” by Jeff Adelson, The Advocate New Orleans

An effort to curb the freewheeling nighttime culture of Bourbon Street by encouraging early-morning revelers to stay inside bars after 3 a.m. is being pitched as a move to increase public safety.

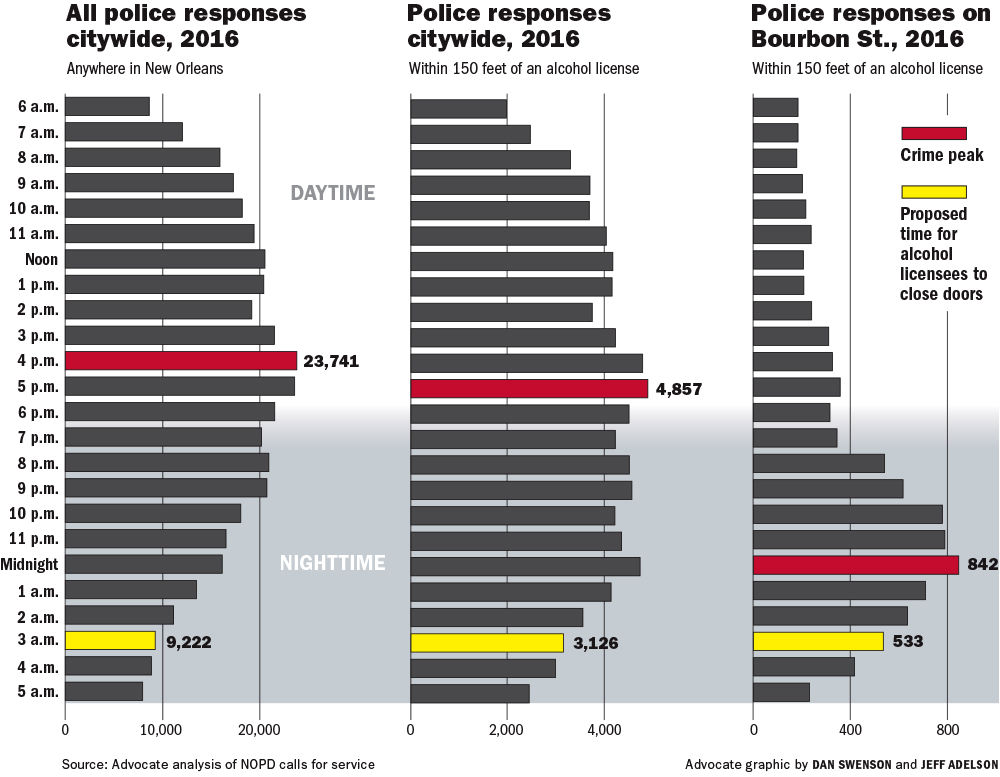

But the plan announced Monday — a step back from an earlier proposal by Mayor Mitch Landrieu’s administration that would have ended the city’s tradition of all-night bars — targets an hour that’s well after crime has peaked and that actually marks the start of a lull in police activity, an analysis of New Orleans Police Department data shows.

All of the headline-making shootings on Bourbon Street in recent years, which served as a catalyst for the administration’s plan, occurred earlier than the 3 a.m. street-sweeping the mayor’s proposal envisions.

In fact, there hasn’t been a reported shooting between 3 a.m. and 5 a.m. on Bourbon Street in at least six years.

The latest version of the Landrieu administration’s $40 million security plan, which includes installing surveillance cameras in 20 neighborhoods and an increased police and code enforcement presence in the French Quarter, does not tamper with the relatively loose rules that allow bars to serve patrons at all hours.

However, it has riled bar owners and French Quarter business groups because, if approved by the City Council, it would require that they keep their doors closed after 3 a.m. and would try to reduce the number of people partying outside — steps officials have said are aimed at both increasing public safety and reducing complaints about quality-of-life issues.

That conforms with what business owners in the French Quarter say has been their experience dealing with crime and crowds on the city’s busiest strip.

“That’s been pretty much our contention: That’s not when most of the crimes happen,” said Alex Fein, with the French Quarter Business League. “The majority of that stuff isn’t happening that late.”

Landrieu press secretary Erin Burns said in a statement that requiring bars to close their doors after 3 a.m. “is one piece of our larger, $40 million public safety improvement strategy that is designed to address the issue as a whole” and that was arrived at “after consulting with several security experts and local stakeholders as well as analyzing the practices of other cities.”

Burns said most of the other cities studied “completely close (bars) at 2 a.m. or 3 a.m., and many of the security experts we consulted suggested that we do the same,” but she added that New Orleans “is a 24-hour city, and we do not feel that closing bars completely would be appropriate for the authenticity of our unique culture.”

However, she said, having bars “simply close their doors at 3 a.m. could encourage people to move inside. We believe this will contribute to a more controlled physical environment, and when coupled with the other security measures in our plan, it (will) allow us to see progress in reducing crime on our streets.”

The Advocate analyzed NOPD records on the more than 404,000 incidents that garnered a police response in 2016, determining when they occurred and how close they were to the roughly 1,500 businesses with a license to sell alcohol.

Those businesses include both bars and establishments like grocery stores and restaurants that likely would be closed by 3 a.m. but that also would be covered by the changes the Landrieu administration is proposing.

The analysis shows that less than 1 percent of all crimes in the city occur within 150 feet of a bar between 3 a.m. and 4 a.m. And of those, fewer than a fifth were on Bourbon Street, the area that would likely be most affected by the proposed changes.

On Bourbon Street, the number of crimes in the hour after 3 a.m. is lower than at any time between 8 p.m. and 3 a.m. That early-morning hour is actually one of the safest times to be outside of a business with an alcohol license anywhere in the city, the data indicate.

In part, the lack of early-morning crimes isn’t a surprise. Relatively few people are out and about at that hour, even in the Quarter and even with no mandatory closing time for bars.

And overall, the French Quarter is relatively safe. The 8th District, which includes the French Quarter and Central Business District, had fewer shootings last year than any other district in the city. While the district does have a relatively high number of calls to police about other crimes, that has to be weighed against the millions of tourists who frequent the area every year, crime analyst Jeff Asher said.

“When you factor in the sheer amount of people that come, it’s not an unsafe area; it’s a pretty good area in terms of safety,” Asher said. “It highlights that the State Police and the NOPD in the 8th District are pretty good at policing that area.”

The administration’s proposal does make sense from at least one perspective. As might be expected at a time when those who aren’t carousing are likely to be in bed and criminal complaints are at their lowest, complaints in and around bars — and those on Bourbon Street in particular — make up a greater share of the NOPD’s workload during early-morning hours than during the rest of the day.

More than a third of police calls between 3 a.m. and 4 a.m. are from within 150 feet of a business with an alcohol license; those same areas make up less than a quarter of all calls over the course of a full day.

One variety of crime does occur in greater numbers in the wee hours: fights, disturbances and simple batteries near bars. At least 187 of those incidents in 2016 occurred near bars after 3 a.m. — about 10 percent of all such cases that police responded to last year. On Bourbon Street, those relatively minor scuffles peaked in the hour after 3 a.m., with a total of 59 cases over the course of the year.

The proposal to close bars’ doors seems misguided to some French Quarter groups. Fein, who owns the Court of Two Sisters and whose group represents 50 businesses in the area, said he applauds the administration’s focus on trying to prevent crime, but he doesn’t believe early-morning hours are the problem.

He noted that while one of his employees was punched in the face recently, that happened at 6 p.m.

Initially, the Landrieu administration approached business owners with a plan that would have marked a dramatic change in New Orleans’ permissive drinking culture: a 3 a.m. last call, Fein said. That was rejected immediately by bar owners, as was the softer version that was in the final proposal announced Monday, he said.

“It sends a message to everyone else that you’re not safe here after 3 in the morning,” he said.

While Fein said his group supports security measures, particularly more police, he said changes to how bars operate could be a major shift for the city.

“It’s what makes us who we are. To be able to come here and have a beer in your hand on the street at 4 in the morning, it’s what makes us unique in the world,” he said. “I don’t know why you’d want to mess with that in any way.”

That sentiment was echoed by the French Quarter Business Association, [a group representing French Quarter] businesses.

“The French Quarter Business Association is opposed to changes to the nightlife culture of the French Quarter,” said Tim Spratt, who heads the group. “A 3 a.m. door closing would change the 24-hour nightlife culture that the world expects from New Orleans, especially in the French Quarter and on Bourbon Street. It simply sends the wrong message.”